What 2009’s The Cove did for dolphin swimming and 2013’s Blackfish did for SeaWorld is what G Adventures’ new documentary, The Last Tourist, aims to do for the tourism industry as a whole.

Over 101 minutes, the film—which is now available to stream on Crave in Canada—takes a deep dive into the voluntourism industry, elephant rides, and foreign-owned resorts, demonstrating the potential and power of tourism to both exploit and uplift communities.

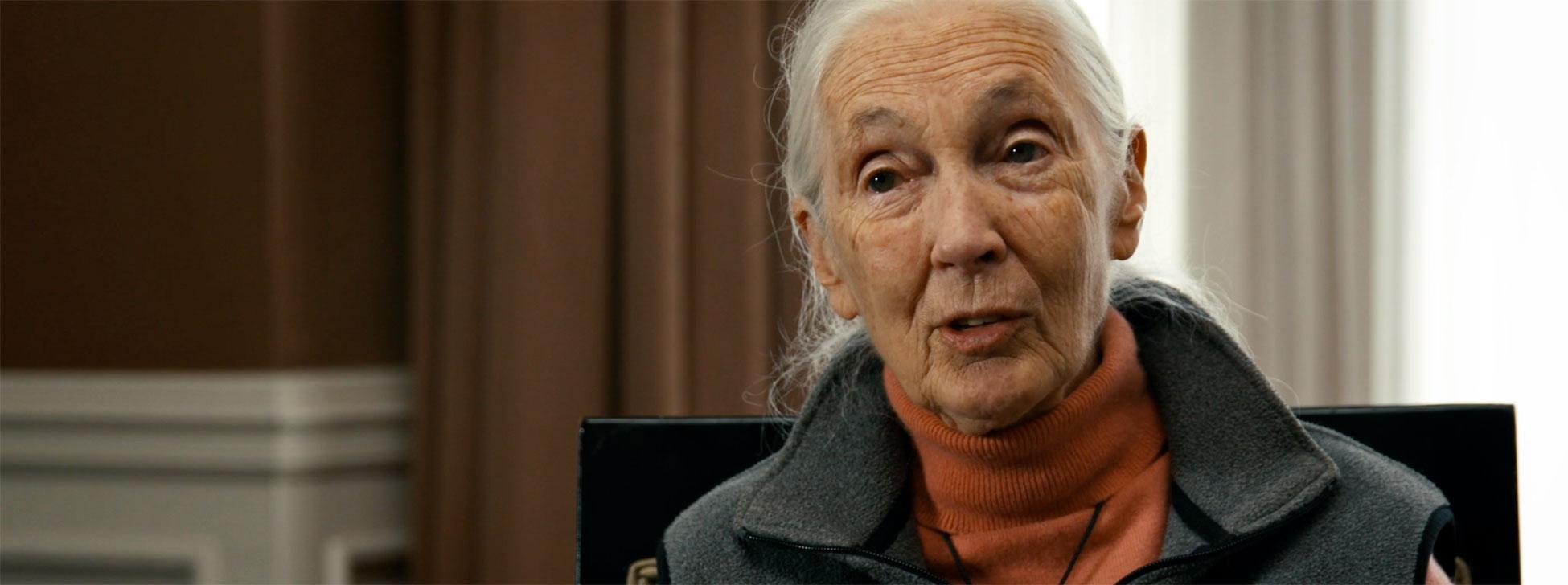

Featuring interviews with travel and tourism visionaries, including Jane Goodall, much of The Last Tourist was filmed before the pandemic. But as travel restarts, its message is more important than ever: Tourism is at a tipping point.

We spoke with writer and director Tyson Sadler to learn more about what inspired the film, and what he thinks the future of travel looks like.

Verge: Bruce Poon Tip, founder of tour company G Adventures, was the executive producer of The Last Tourist. Was it difficult to direct a film that was funded by, yet critical of, the tourism industry?

Sadler: The film was editorially independent. But, a lot of guidance came from G Adventures and a lot of inspiration came from Bruce’s views on inclusive travel. I set out across the globe to find people who identified similarly in terms of that ethos—which just so happens to be my ethos. So, it wasn’t difficult to build a film around that, because we were all in line.

We wanted to uplift the travel community as a whole and create something larger than G Adventures. Think of what Al Gore's 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth did for the global conversation around our relationship with climate change—we really want to make something like that, something universal and global, but with the travel industry.

The movie focuses heavily on the pitfalls of animal entertainment and voluntourism, and foreign-owned hotels. However, it doesn’t examine other issues in-depth, such as tourism’s carbon emissions. How did you decide what themes you want to focus on?

In early 2018, I did a deep dive and read every book that I could, consuming information at a rapid pace. I knew I wanted to have some of the world’s foremost thought leaders in terms of conservation, environmental stewardship, and wildlife preservation, who all support the same message.

The Last Tourist is meant to be a spark that ignites the flame within people to have challenging and difficult conversations about the way we travel.

There was some push and pull in terms of what kind of themes we wanted to tackle, including some that were just too big a mountain for us to climb. But, I recognized early on that the main pillars of responsible travel include the impacts of tourism on wildlife, the environment, and host communities.

A lot of these themes weren’t necessarily new at the time, but it did give me an opportunity to dive deeper into what is the true cost of taking an elephant ride? What is the true cost of going on a cruise ship? What is the true cost of inexperienced and unqualified travellers volunteering with vulnerable populations, like children abroad?

There were other stories and themes we had to cut—like gender equality within the travel industry, and women porters on the Incan Trail—because we had to whittle 400 hours of footage into a 90-minute film. I hope someday those stories will be told because they’re valuable and important. I think this needs to be a six-part series for video-on-demand, because we can dive so much deeper into the environment, into gender and equality and into poverty alleviation.

You filmed the Last Tourist in 16 different countries. What were some of the responsible travel practices you adhered to while on the job?

We wanted to practice what we were preaching. We always stayed in local hotels—never in chains—and we preferred mom-and-pop restaurants for the authenticity of the experience.

We had a core crew that was Canadian, but hired local mixers and always had local partners in the areas we were travelling to. We couldn’t have done it without our knowledgeable and helpful local partners on the ground, whether we were in Cambodia, Thailand or Kenya.

How did the pandemic affect The Last Tourist?

Around January 2020, the film was completed, and it was getting ready to go to colour. And then in March, flights were grounded, and borders were closing. We realized that we couldn’t have a conversation about travel and tourism without talking about the impact of the pandemic. The film was already out of date. We could have released it, but there would have been a glaring hole in it.

So, we added an additional 12-minute segment that explores the impact of the coronavirus on global travel and tourism, and addresses the question, “What would happen if travel and tourism were to stop today?”

The pandemic was terrible, but it did give us an opportunity to see the impact that stopping the travel industry had on some of the individuals whose stories we share in the film.

What do you hope the film achieves?

It’s been wonderful screening this film at festivals, because the post-screening Q&As are very insightful and thoughtful. It’s evident that there’s something in the film that connects with audiences on a very emotional level—whether it’s about wildlife, children or poverty relief, it strikes a chord.

But The Last Tourist is just a jumping-off point. It’s meant to be a spark that ignites the flame within people to have challenging and difficult conversations about the way we interact with destinations. I want people to hold a mirror up to themselves and ask, “What have I been doing? Has it been sustainable? Is there anything that I could do better? Is there a way for me to reduce my impact when I travel abroad?”

For me, that’s how I feel. Every subject that we approach in this film, I’ve been guilty of in the past. I’ve ridden elephants and volunteered in orphanages. I’ve been on cruises. But I didn’t realize the ripple effect that these activities had. It wasn’t until I made this film that I actually recognized the impact that my travel choices had. And I hope our audience approaches the film in a similar way.

With tourism restarting now, do you think we’re going to see any changes?

Some of the largest travel demographics on the planet aren’t having the conversation about responsible tourism, and they might not be having it for another 20 years. I think it’s a conversation among millennials and younger travellers, but globally there are other populations who haven’t even begun this conversation yet.

We still have a great battle to fight and this film is just one piece of this larger battle. I think we’re headed in the right direction, but we still have a very large mountain to climb before we can say the tourism industry is sustainable or responsible.

If people were going to take away one key message, what would you want it to be?

With knowledge comes responsibility. We actually have a responsibility to make changes in our travel habits and share the message of ethical travel with our circles of influence and with our friends and family.

Add this article to your reading list