At an altitude of 4750 metres, the wind—which was soft and warm at the base of the mountain—blows with the ferocity of a Canadian storm. In the early morning, the ground is covered with a morning frost and snow has begun to fall. Imagine yourself there—but wearing just worn sneakers and a thin spring jacket. Sadly, such is the reality for many of the porters who work on Africa’s highest mountain, Mount Kilimanjaro.

Though stories of children as young as nine and mature retirees who have reached the summit have augmented the mountain’s mythical accessibility, the climb is difficult. In fact, of the approximately 20,000 people who attempt the climb annually, only an estimated 40 percent are successful.

I am one of the lucky ones to escape physical injury and altitude sickness to reach Mount Kilimanjaro’s Uhuru Peak. Not that I did it alone. For our group of two people, we were assigned nine crewmembers—a ratio that even the Kilimanjaro Porters Assistance Project would be pleased with. They suggest a 3:1 minimum. Our crew includes a guide, cook and seven porters.

Having made the trip more than 50 times, our guide, Florent, is an old hand. But asked about his first ascent, he quickly debunks the Western myth that locals find the climb any easier than the tourists. He made his first trip as a porter at 23 years old and like many of the locals, he had never been on the mountain before his first day of work.

“I didn’t get sick on my first trip because I only went to Kibo Hut [at an altitude of about 4730 metres] with the rest of the porters and didn’t summit,” he recounts. Florent’s eyes, the only feature that reveals his age and experience on his otherwise youthful face and wiry frame, are thoughtful as he explains. “But on my sixth trip, I went as a summit porter because I had experience and could speak English—and I got hypothermia because I didn’t have the proper clothes.”

Porters like to be chosen for the summit climb because, although it is the most physically challenging part of the trip, it increases their earnings. Having a summit porter costs the group at minimum an additional $30 but the assurance it provides it is well worth the money. Should one of the climbers fall ill, they are able to descend with the summit porter while the others continue—and it is here on the steep switchback trail of the final ascent where most people falter.

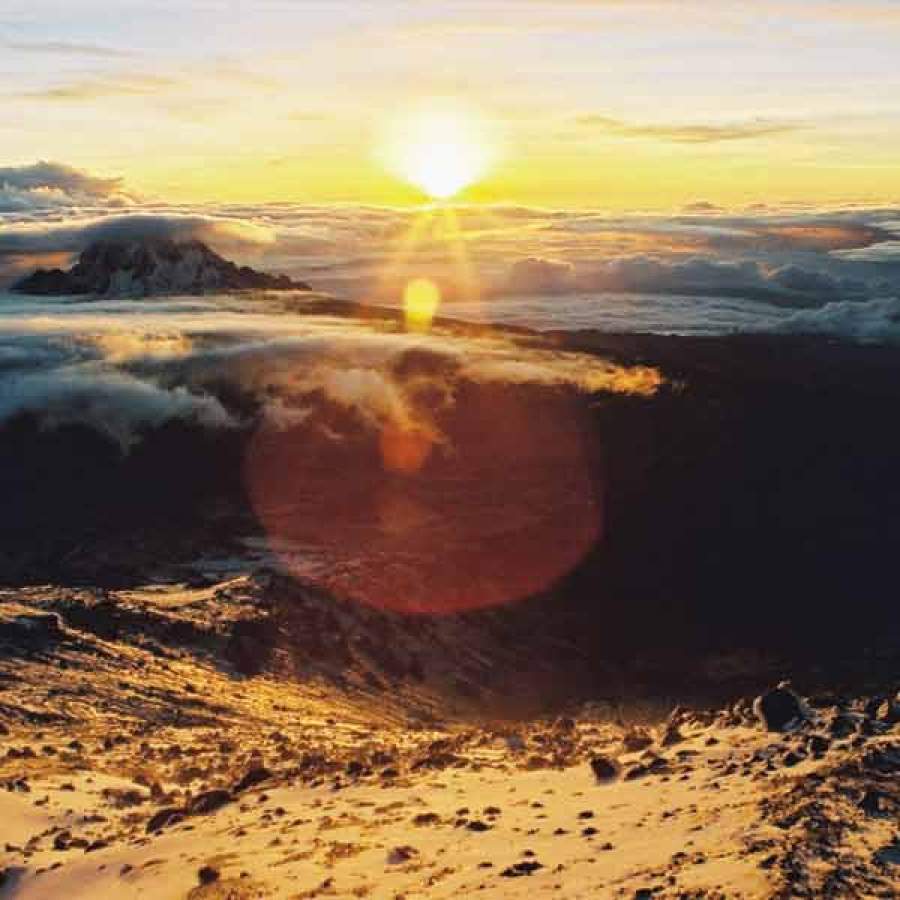

The opportunity to earn the extra cash may prove too tempting for some whom, like Florent on his first summit, attempt the climb without the proper gear. Most groups make the six-hour summit climb at night, starting shortly after midnight. In the night-time darkness, the climbers can see only what the glow of their flashlights reveals, a fact the guides use to their advantage.

“When my group asks me how much farther it is to the top sometimes I tell them it is only another hour even though I know it may be more,” Florent reveals. The darkness that conceals the top of the mountain from view also conceals Florent’s fib. It is a tricky tactic perhaps, but one that, at a time when each step feels like a 100-metre sprint and every minute feels like an hour, I sincerely believe got me to the summit.

Regardless of its apparent advantages, climbing at night also means the temperatures are lower—low enough that despite three pairs of socks and my Gore-Tex gloves, my fingers and toes alternate between numbness and painful prickling on the trek up. Not even the night-time darkness can conceal the need for everyone, porters included, to sport the proper attire.

"I went as a summit porter because I had experience and could speak English—and I got hypothermia because I didn't have the proper clothes."

Theoretically, there are regulations in place to ensure that the porters have the proper gear, including clothing, shoes, shelter and sleeping equipment, yet I saw more than one pair of battered sneakers and thin jackets on the mountain. The paths on the main routes are wide and well maintained; nonetheless, the porters carry upwards of 25 kilograms of equipment. Having watched my own porters strap this equipment on—their own packs on their backs, our bags, tents, food and cooking supplies balanced on their heads—I suspect that this would be a difficult feat in sneakers held together with duct tape.

The expectations are the same of all the porters, regardless of their size. Small and slight of build, Paulo, the smallest of our seven porters, is nonetheless able to carry the required weight. His looks belie his age and although he is in his mid-twenties he appears about 15 years old. He is a constant flow of words—singing hymns and teasing the other porters as he helps prepare the meals, peppering us with questions to try to improve his English. He is just a porter right now but he is apprenticing to become a cook. Cooks have greater earning power as they are fewer in number and they are sometimes used on safari tours as well.

Poor wages here are a simple issue of supply and demand. Tourism is a major industry within the Kilimanjaro region yet, as more and more young men flock to the area in hope of employment, the problem of too many workers and not enough customers is endemic. Most companies rotate their guides and porters, which means that they rarely have more than one job per month and sometimes none at all. It isn’t salaried work and so these slow periods make for desperate times.

So what can you as a tourist do to help ensure that your own crew is treated fairly? First and foremost, ask the tour company directly how they treat their guides and porters before you book your trip. For a comprehensive set of guidelines on proper porter treatment as well as a list of reputable tour operators check out the International Mountain Explorers Connection (see the sidebar for more info).

Additionally, be aware that tips constitute much of the crewmembers’ wages. The standard guideline dictates that you should tip the crew 10 percent of the amount you paid for the entire trip but, as Florent hints diplomatically, “Canadians and Americans usually tip more.”

Choosing a reputable company may cost you more money, but as you watch the sun rise across the glaciers at Mount Kilimanjaro’s peak you will be able to rest assured knowing that you did not get there via the exploitation of your porters.

Learn more about treating your porters with respect.

Add this article to your reading list