“It was the right thing to do after recovering from my illness,” says 73-year-old Aristedes Zeledon. He’s standing proudly on a ramshackle porch, his bronzed life-hardened face split between light and shadow. Aristedes is explaining his simple motivation for building a quaint church for the local farmers’ families. His stories of community benevolence, of Nicaragua’s past civil war, of his family and his recent illnesses, make me forget about the chomping bugs and searing midday heat. Two themes run through his anecdotes: drive and hope. And there’s a good reason why Aristedes exudes such optimism—he is a Nicaraguan fair-trade coffee farmer.

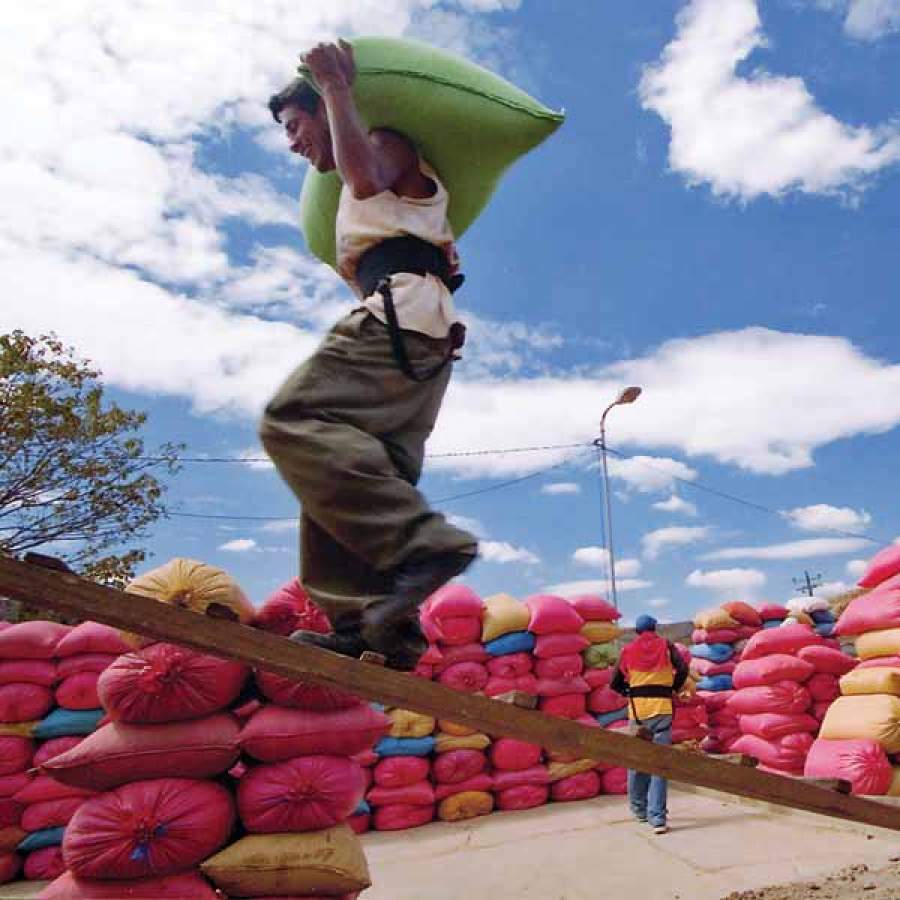

Aristedes lives in the fertile Samulali region of Nicaragua, Central America’s largest country. He is among a growing number of coffee farmers in the verdant mountains near the northern town of Matagalpa who are affiliated with The Organization of Northern Cooperatives, or CECOCAFEN. The organization helps small-scale Nicaraguan coffee farmers, like Aristedes, find buyers for 70,000 sacks of beans each year in order to obtain a higher price (“fairer price” in Aristedes’ words) for their coffee beans.

“We are a business-oriented organization that seeks out better market conditions for members,” says Felicity Butler, a British-born coordinator of the rural and community based tourism project at CECOCAFEN. I have been invited to Nicaragua by Felicity to learn about the agricultural and social benefits of fair-trade coffee production and to participate in their latest venture—the agro eco-tourism project.

On this atypically damp January morning, she is sitting with me at the organization's headquarters in Matagalpa, talking about the ambitions of this unique tourism experiment, launched in 2003. “We put visitors in direct contact with the faces, voices and culture of the farmers who produce their coffee,” explains Felicity. The project affords people from the overdeveloped world—like me—the rare opportunity to sleep and eat in farmers’ homes, learn how to cook traditional food, hike amidst the lush surrounding countryside and learn about hard work that goes into producing coffee.

Felicity peaks my interest when she informs me that tourists are encouraged to participate in the entire coffee production process, from picking the cherries—the ripe red coffee beans—to sipping the brewed java. Suddenly, I can hardly wait to start my home-stay with the farmers. Felicity sets her eyes on me and says brightly, “You’re in for first-class hospitality.”

My first night in the La Corona community is spent in a modest adobe house. With light coming only from the gleam of a well-worn lantern and an almost supernatural canopy of stars, I find myself discussing coffee farming and life in Canada with 58-year-old Juan Acuña. He is a congenial, slight man who has poured his own blood and sweat into his 17-acre farm. The only thing keeping him busier than producing specialty coffee is watching over his nine children and, as Juan puts it, “lots of grandkids.”

Four Nicaraguan fair trade communities (La Corona, El Roblar, La Pita, La Reyna) now open their doors to tourists so that a face and voice can be put to that cup o’ joe.

And farmers like Juan are keeping their fingers crossed that this will help to diversify their incomes. Although the programme is in its infancy, with only a few visitors, growing interest in community and eco-based tourism is likely to make this endeavour an effective one.

It's a win-win outcome: I take home the experiences necessary to promote fair trade, and community members have a chance to improve their standard of living.

Fair trade does deliver many social, economic and environmental benefits to Nicaraguan coffee farmers, but it still falls short of helping families meet all their financial commitments. The additional benefit of tourist greenbacks is clearly evident. The community of La Pita, with 15 coffee-growing members, is using funds from the tourism ventures, plus low-interest loans from CECOCAFEN, to grow organic vegetables, buy mosquito nets, provide purified water, teach English to future guides, build extra rooms to house tourists, and purchase school supplies. It’s a win-win outcome: I take home the experiences necessary to promote fair trade as a real and viable alternative, and community members have a chance to improve their standard of living, and invest in environmentally sustainable technologies that keep their surrounding countryside flourishing.

Climbing the nearby slopes, we see firsthand some other benefits of growing coffee organically, under the canopy of shade-giving trees. Groups of green parrots exchange perches overhead, and it is clear that that using tourism and fair trade dollars to plant native trees is a boon not only to the coffee bean, which requires shade to mature properly, but also to the spectacular multicoloured birdlife.

“Don’t tear off the stem or no bean will grow there next year,” we are told by a community guide as she instructs us on the proper way to gather mature cherries from the trees. For the next hour or so, as the mercury sneaks upwards continually, a bunch of sweaty gringos attempt to fill baskets tied snugly around their bellies with what looks like spilt candy.

It’s humbling work. Two buckets of cherries is all a group of 25 manages to collect. Our payoff? Thirty-six Cordobas—or about two American bucks, according to Sergio. I get the feeling that one motivation for hosting tourists like me is so that people in my country begin to learn how hard people work to produce their coffee.

Back on level ground my hostess, Tomasa, rustles me up a plate of locally grown organic kidney beans, squash, salty cheese (cuajada) and corn tortilla. She is a shy twenty-something farmer with a prominent silver front tooth, In my best broken Spanish, I ask her what she likes most about living in this community. Answering my question in even more fragmented English, she states simply “it happy place.”

It’s then that I realize opening my wallet to farmers like Aristedes, Juan and Tomasa—with their unyielding commitment to family, the environment and producing a quality product—is money well spent.

Interested in visiting fair trade coffee cooperatives in Nicaragua? Visit the tour website here.

Want to learn more about fair trade? Visit the TransFair Canada website here.

Add this article to your reading list