The Happy Healing Home outside of Chiang Mai, Thailand, is famous for a few things: its amazing farm-to-table meals, a bad-tempered water buffalo, and Pinan Jim’s righteous tunes (in English and Lanna).

I spent some time there with Margaux and Tyree, two students researching permaculture, and learned about the transition from the modern gadgetized world to the subsistence life.

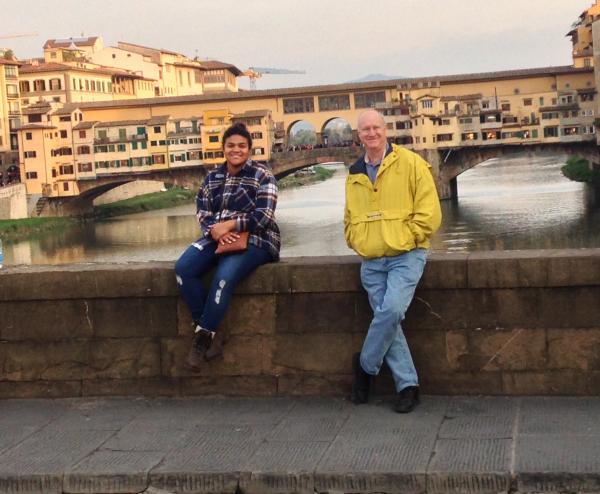

Marguax and Tyree are students at Centre College, where I work. The college integrates course work, study abroad, international internships and career placement into a continuum, where students no longer experience travel and study as divisible, one-off experiences. Margaux and Tyree participate in Centre’s Asia and the environment track, which has taken them from coursework on campus, to study abroad programs in Thailand and Malaysian Borneo.

Despite being tough and active, both Margaux and Tyree talked about how humbling it is to have to be taught everything from scratch. They’re great students and capable musicians, eager to learn and assist, but they come crashing against their limitations when they’re asked to do even the simplest tasks on the farm: carve a pineapple properly, plant rice on slopping terrain, take the buffalo to water, etc.

There’s always a lingering feeling of being a bother to Jim and his family, even more so as they insist on lending a hand. As director of our college’s international programs, I often witness insecurity and awkwardness emerging from immersion experiences. The unfamiliarity of living within a subsistence-based experience can rightly aggravates feelings of disorientation and inadequacy.

I often witness students' insecurity and awkwardness emerging from immersion experiences. The unfamiliarity of living within a subsistence-based experience can aggravate feelings of inadequacy.

Margaux and Tyree seemed discouraged at times, doubting the value of their contribution. I, however, saw something much different happening.

After being at the Happy Healing Home for only a short time, Margaux and Tyree looked like they were running the place: organizing an assembly line to prepare food and wash dishes, fixing bamboo huts and mowing grass with hand scythes. One of my evening tasks was to help the family repair a rotted-out kitchen prep table. Tyree joined me and proceeded to detail a quick blueprint and process for obtaining and preparing the wood, and efficiently swapping out damaged pieces. She grabbed a homemade hatchet and hand saw, cut a couple of logs to size, knocked off some knots and dug a hole for a new post. In under an hour, we had the fresh wood nailed into place and the table (practically) level and ready for dinner (a beautiful spread of fresh fruits, rice, chicken and salsas).

Humility can seem fairly one-sided when we experience it; we feel inadequate and flawed when out of our element. Sadly, I’m pretty sure we don’t see how that motivates us to try harder and achieve more.

For all their perceived shortcoming as novice farmers, the fact that Margaux and Tyree can already plant bananas and rice, care for chickens and water buffalo, fetch water from nearby ponds and wells, mend fences and bamboo huts, and finally repair furniture with logs from the forest is reason enough to allow ourselves to linger in new places and to let humility motivate us to greater accomplishment.

Add this article to your reading list