I'm not surprised to hear that foreign aid pays for sixty percent of public expenditures in Laos. Every time I get on a bus, I end up sitting beside an international NGO worker. First there's the Korean mushroom expert, who is spending two years growing spores on Petri dishes on the outskirts of Vientiane. Then, the guy who used to install solar panels to bring electricity to remote areas. One night I walk into a gay bar and meet a British UXO removal expert, who explains to me in great detail the difference between unexploded ordnances and landmines. Some pick-up line.

It's payback time, for sure: Laos has the distinction of being the most thoroughly bombed country (tonnes of munitions per person) in history. During the "Secret War" between 1964 and 1973 the U.S. ran almost 600,000 sorties and dropped nearly two million metric tonnes of bombs, to prevent pro-Vietnamese forces from gaining control of the area. Before that, French colonizers imposed forced labour, kept locals out of the civil service and did little to develop the country. Today, there's a lot of catching up to do in education, health care and economic diversification.

The interesting thing about NGOs in this country is how approachable they are and how easy it is for the casual visitor to get involved. Wandering through the gift shops in Luang Prabang, I come across a booklet called "Stay Another Day," which explains how tourists can help in just one day. They can pay for a traditional steam bath and massage at the Lao Red Cross and donate a pint of blood. In Vientiane, Les Artisans Lao invites visitors to tour their production centre and give advice on marketing, packaging and chemistry. The Lao Rugby Foundation wants tourists to join in a school training session.

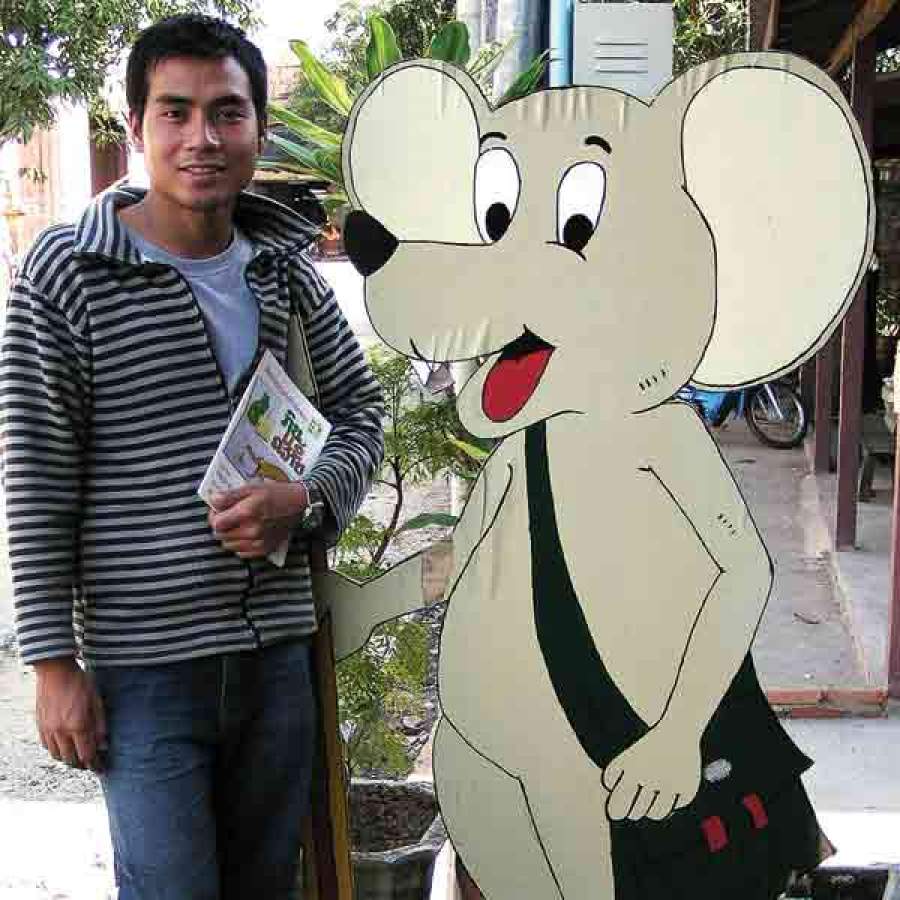

Wondering what kind of impact this drop-in voluntourism can have, I visit Big Brother Mouse, a Lao-owned enterprise that creates picture books for local children. It's easy to find in Luang Prabang, with a big cut-out figure of a mouse in front. A table holds dozens of colourful books in Lao and English, with titles like “The Bag of Smiles,” “The Cat that Meditated,” and “Hmong Life Colouring Book”.

Volunteer advisor Sasha Alyson, from Boston, says that on his first visit to Laos he noticed the only books children had in their language were dry textbooks. He was travelling with a copy of “The Foot Book,” by Dr. Seuss. "I read it to so many people, I knew it by heart."

He talked up the concept of books being fun, and met Khamla Panyasouk, who wanted to lead the effort. They decided to structure the organization as a small business rather than an NGO.

"I've seen too many NGOs where the primary focus of the staff seems to be keeping a comfortable job. As a business, even one where much of our income consists of accepting donations to get books into villages, we have to get results," explains Alyson.

They began producing picture books, in Lao, Khmu, Hmong and English. Local staff wrote and illustrated many of the stories with local readers in mind. In “Baby Frog, Baby Monkey,” one of their first books, Alyson was surprised to see baby animals eating other animals, but he soon realized that was okay here.

Travellers can purchase books and distribute them in towns and villages. At the office, they can help with English conversation and homework for students who hang out in the mornings. Visitors who are committed to a longer stay may be able to do computer work or assist staff with writing and translating stories.

The volunteers are ready and soon a group of students arrives for conversation. A young American takes a globe and shows a couple of boys the location of Guatemala, which they're studying in school. Then they find Iceland and talk about hot springs and geothermal energy. A feisty Swedish senior helps staff translate children's poetry from Lao into English for a possible new book. Meanwhile, another volunteer is having a hard time fitting into the easy-going Lao rhythm as he helps a student with homework.

"Well, are you starting it?" he asks the student, who's flipping through a dictionary.

"What are you doing? Let's get started. Let's do it now," he continues, while the increasingly flustered student tries to preview the vocabulary he will need.

Another contribution visitors can make is to sponsor a book party: $250 to $350 pays for a crew of animated staff to drive out (or, in many cases trek out) to a village and distribute dozens of books. The sponsors get to accompany and help. I score an invitation to the next book party, happening in the village of Houa Kaeng.

Early in the morning, we pile into a minivan and head north from the city. There are the sponsors (a couple of newlywed New Yorkers), and four young staff. Sonesoulilat and Lineda sit in front. Yuphin, who wears a sweatshirt marked “LA Today Girl” stretches out in the back and sings along to Thai rap music. Link sits beside me and talks about the shortage of medical facilities in Laos.

We turn off the highway onto a series of deteriorating gravel roads, and suddenly we're there. The first thing I notice is a wat-in-progress, an unfinished temple with bricks and rebar reaching to the sky. Beside it, a truckful of young monks is parked next to a carpet on which people are kneeling. We continue up a hill and stop at a new primary school complex with three sturdy concrete classrooms, full of desks and uniformed children.

The children start chattering with excitement, and the staff go right in and begin the program of songs and lessons. We three falang have our cameras out, but we try to be unobtrusive—every time we stand too long in a window, the children turn around and stare at us.

Villagers gather to see what's going on, mothers and grandmothers with babies in arms. An old woman tells me the newborn she's holding is an orphan whose mother died in childbirth. The woman coughs, a deep, phlegmy rasp.

"I've seen too many NGOs where the primary focus of the staff seems to be keeping a comfortable job. As a business, even one where much of our income consists of accepting donations to get books into villages, we have to get results."

Suddenly the children fly out of the classrooms and race towards the playing field. The staff arrange them in a circle and tie them together in pairs for a three-legged race. One pair wears bright pink masks: the theme is tooth decay and they're the germs. The germs proceed to chase the other pairs and tag as many as they can.

After a few more games, the children race back to some outdoor tables where they receive an orange and a glass of orange juice. Then they go back into their classrooms for story time.

Meanwhile, Yuphin is quietly laying out a hundred picture books on the tables. A few feet away, Link is pounding a series of pegs into the dusty ground and attaching them with string, to construct a no-go barrier that the children will have to stand behind while waiting their turn to select a book. It looks like a customs line at an airport, where travellers wait to enter a new land. In a way, that's exactly what it is. For most of these children, this will be the first book they've taken home, the first fun book they've ever seen.

The connection is becoming clearer to me, the reason why organizations like to have tourists drop in for a day. After thumbing through a few books they may feel inspired, like these New York newlyweds, to sponsor a book party. When they go home and show off their photos, friends of theirs may want to do the same.

The books are laid out on the table and the string barriers are ready. Sonesoulilat gives the signal and the children race out of their classrooms and fling themselves at the tables. Quickly they are herded into tidy lines behind the string. The air is thick with anticipation, the children quivering as they strain against the string, bending it to the max. One girl licks her lips.

In small groups, the children are called up and, they select one book each, their faces set with concentration over this momentous decision. Silence reigns and the children stroll away happily, their faces buried in the books.

Add this article to your reading list