“I want to go to university to study hotel administration and work in hospitality, and then maybe in the future become an accountant,” Juana tells me, her eyes lighting up with the prospects for the future.

It is my first interview in Spanish, and as I speak (and later, when I listen back to the recording) I cringe at the Britishness of my accent, and how stilted the words sound at times. Juana—my young interviewee—doesn’t appear to be much more comfortable, and it’s frustrating that my lack of fluency is preventing me from putting her at ease.

Gaby, the director of The Sacred Valley Project, who lives with the girls during the week, has told me that it’s a big deal that Juana has even agreed to do the interview. Normally she doesn’t like to talk about herself with people that she barely knows.

For the interview, I am in the town of Ollantaytambo in The Sacred Valley. Known affectionately as Ollanta by the locals, it’s often just a brief stop on the tourist trail between Cusco and Machu Picchu. Seeped in history—impressive ruins and Inca terraces overlook the town from every direction—it remains a small, quiet place. Once you step away from the main square, it’s easy to forget the existence of the dozens of tour buses arriving here each day.

For rural Peruvian students, the choice is between travelling to school in the nearest town and back each day, or not going at all.

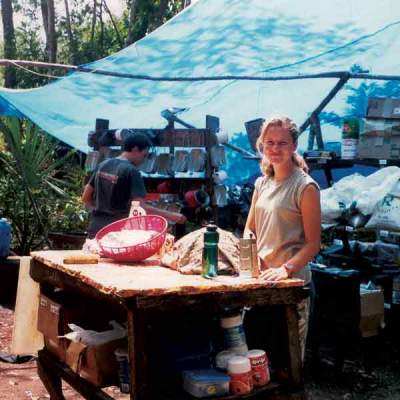

Over the past three months, I’ve visited Ollanta regularly to deliver workshops with LAFF. Hidden away from the main streets of town, The Sacred Valley Project’s house or albergue is located along a dirt path lined with fields of bloated corn and the occasional roaming bull. Perched on the very edge of the River Vilcanota, the views from the gates extend for miles back along the valley.

Established in 2009, The Sacred Valley Project is a charity seeking to empower young women from indigenous communities by providing them with a place to live and the economic means to access education. Girls demonstrating academic promise, but who come from distant rural communities without schools, will live in the house for free during the week and return to their homes, and families, at weekends.

It is a small space, housing just under 20 girls, and centred on a grassy space with a volleyball net. The dormitories peel off to the left and the main kitchen, which doubles up as workspace and dining area, is straight ahead as you pass through the gates.

Today I’m meeting with Juana, the oldest of the girls. At 18, she finishes secondary school this week and is preparing to leave the house. As part of the second cohort of girls since it opened, she has spent the past five years living here.

The uncomfortableness of the interview is shifting slightly as Juana talks to me about her family. She is one of nine siblings, but only she and her younger sister still attend school. I should—but I don't—ask about how her sister affords to attend school and live in Ollanta, since she doesn’t have a place at the albergue.

The rest of her brothers and sisters, all brought up the same far away rural community, now live in various towns dotted along The Sacred Valley. Given that jobs in rural Peruvian communities are often farming for the men (like Juana’s father) or becoming housewives for the women (like her mother), it is unsurprising that they’ve looked for other opportunities.

What strikes me is the nonchalance with which Juana speaks about her community, but more importantly, her journey to and from each weekend. It is “a distance of six hours away. You have to take a car for two hours and then walk the rest.”

For her, this is a mere statement of fact: all of the girls in the project travel similarly staggering distances, often by foot, alone, and for the prospect of a mere 36 hours or less with their families. But for me, this is a demonstration of her commitment to education that I couldn’t begin to imagine from the vast majority of my previous students in the UK.

It is this drive and determination that permeates our conversation. When I ask whether she enjoys school, she chides the discipline system, saying, “I like school, and all of the teachers try and teach me the best they can, but the head teacher doesn’t do enough to punish or expel those who mess around in lessons: they always give them another chance.”

Along with the other girls in the albergue, Juana seems very conscious of the opportunity she has been given with her place at The Sacred Valley Project. For rural Peruvian students, the choice will be between travelling to school in the nearest town and back each day, or not going at all.

While improvements in education are being made, it remains that the location of your birth will affect your education and subsequent life opportunities. Statistics published by UNICEF show that despite 73.2 per cent of urban Peruvian young people finishing their secondary educations, only 42.3 per cent of rural students achieve the same. Without places in the albergue, most of the girls in the project would have given up education at the end of primary school.

With this in mind, I want to know how Juana feels the project has impacted upon her life, and where this change has come from. With little hesitation, she gestures towards Gaby.

“It’s because of Gaby that I hopefully can go to Mosqoy [the project that may support her with her university fees]. She’s given me so many opportunities”.

Gaby has been working quietly on her laptop throughout the conversation, but now looks up and smiles. She is personally responsible for the familial and welcoming air that you encounter as you cross the threshold, and it is evident from the relationship between the two that she has been a powerful force in supporting Juana over the past five years.

She is keen to tell me why she is so proud of Juana.

“It’s incredible what the girls achieve here; they move at the age of 11 to spend all week away from their families. That’s an enormous step for such young girls, and all in the pursuit of a good education. But in Juana’s case, it’s been even more.” It is clear that Gaby is struggling to contain her emotions.

“It takes Juana six hours to get home. Six hours every Friday and Sunday. She doesn’t get to her village until gone 9pm—she has to walk through the forest at night to arrive. But she’s had so many other challenges that she’s dealt with.” They both begin to cry: Gaby out of pride, and Juana perhaps from the realization that her days in the house are numbered and it’ll soon be time to move on.

“One summer holiday, Juana couldn’t go home because of problems with her family situation. So instead, she spent the two months living by herself, working to earn the money that would support her studies for the next academic year. It’s incredible what she’s overcome.” Gaby gets up and goes over to give Juana a hug.

Both seem to be coming to terms with Juana’s departure from the house, although if she manages to secure a place at Mosqoy—another organization that provides board and financial aid for university students from indigenous communities—she’ll only be a few hours away by bus. I ask her if she’ll be coming back to visit, and she nods through her tears.

As I leave—hugging and kissing both as is customary here in Peru, but perhaps with a tighter squeeze than is usual—Juana is still wiping the tears from her eyes.

I head back into the main square and play back our conversation in my head. I find myself still stunned and humbled by the diligence and determination that is driving these young women. It is their commitment to the pursuit of a good education that is inspiring, and the hard work of The Sacred Valley Project to support them in doing this leaves me with no questions about the girls' future prospects.

Some names have been changed.

Add this article to your reading list