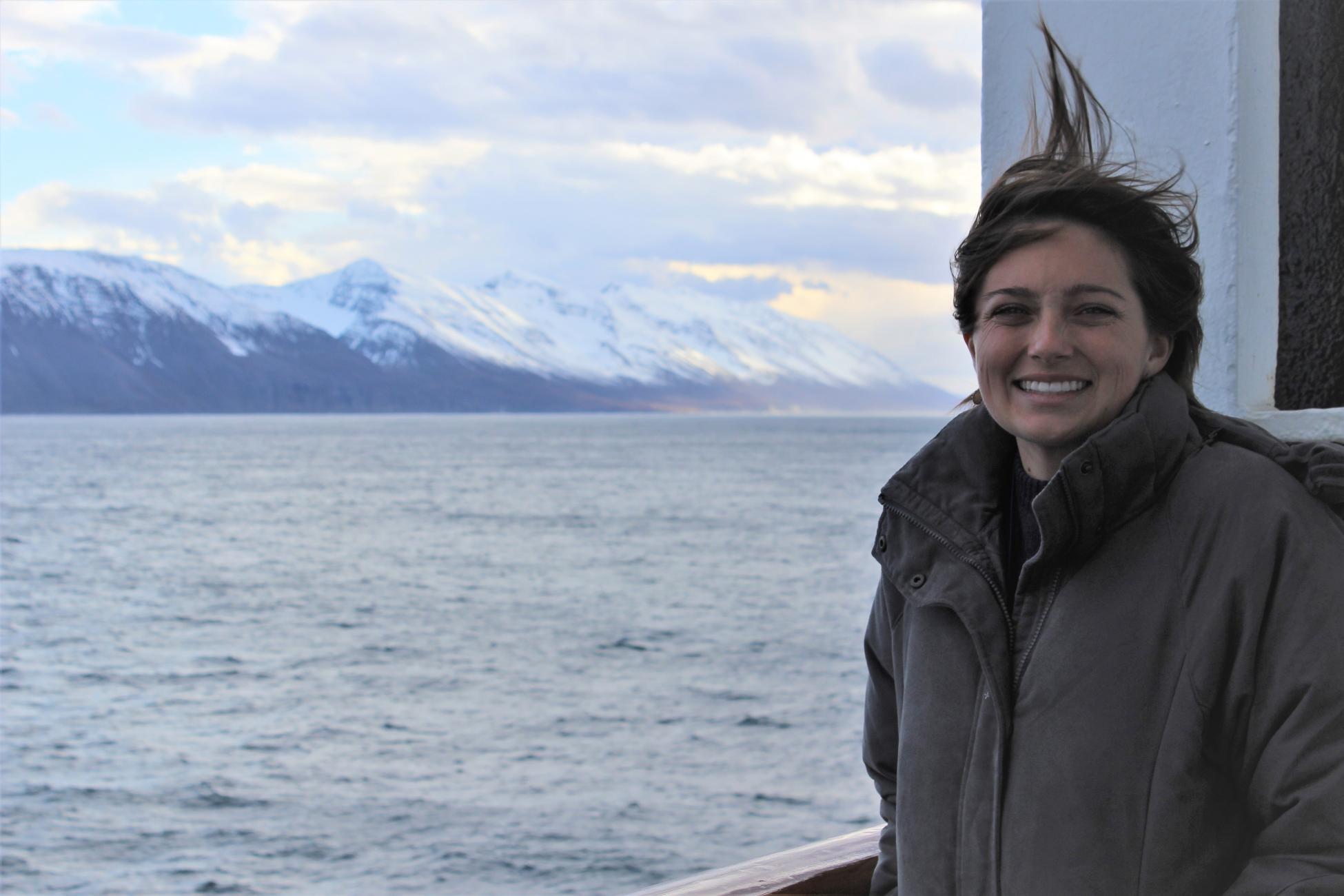

Stepping out onto the open deck, the gentle sea breeze caresses my face. Turning to the sun, I smile and close my eyes as it warms my cheeks. Today, the sea looks like glass as our 35,000-tonne ship cuts through it. I look to my left—nothing. I look to my right—nothing. That's when I realize that I'm miles and miles away from any semblance of land.

Every now and then I can see cargo ships passing in the distance. Some areas of the ocean have much higher traffic than others. I get the sense that we're travelling in our own lane, parallel to unknown vessels.

For some passengers, it is a bit unsettling to feel so far from other ships, land, and loved ones on land. Personally, it feels freeing. You can see for hundreds of kilometres in any direction, and all you see is water.

When I am on the open deck, I often wonder what it must have been like to truly be "disconnected" from the rest of the world; to send a letter, and not know for months whether or not it was received.

I remember reading a passage from the book of letters exchanged between Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre during the early 1900s. They were to meet up in Paris after having spent quite some time apart. Beauvoir essentially wrote Sartre a letter with a list of the places where she might be throughout the day, so that when he arrived to town, he might know where to find her. There was no certainty as to where or when they would meet. If anything came up that even ever-so-slightly changed their plans, there was no immediate way to communicate with the other.

I envy this type of communication. It's a kind I feel lends itself to adapting to the unfolding of events, rather than correcting every detail the second a change in the original plan arises.

Volunteering on Peace Boat has given me a glimpse into this way of communicating. Even though I come from a rural town, and have camped in remote areas, I have never spent so many days with no access to internet or phones since I was a child. Having been born in the '90s, I have only known a world with text messages, WiFi, and live video chatting.

Once I boarded the ship, I felt immense relief because I finally had a "legitimate" excuse for replying to messages in an untimely manner.

It is possible to purchase a WiFi card on Peace Boat, but depending on factors such as proximity to land, it may or may not work well. Cell phone reception also depends on proximity to land and the type of phone plan you have. Personally, I decided to opt out of the WiFi card, and seeing as I don’t have a phone plan, I am not able to communicate with anyone off the ship until I arrive in a port.

Of course, this does present a challenge when I am meeting friends or family in port. I have been extremely fortunate to meet two friends of mine throughout the voyage thus far: one in Liverpool, and another in both Italy and Iceland. Luckily they found the correct dock, and we were able to meet each other right away, but just like Sartre and Beauvoir, it wasn’t without some wandering around until we ran into each other.

Generally speaking, I have never been great at keeping up with social media or replying to instant messages. Once a few days would pass, or even a few weeks, I would begin to feel stressed out for not responding to a message. So, once I boarded the ship, I felt immense relief because I finally had a "legitimate" excuse for replying to messages in an untimely manner. The stress I had felt before subsided, because I am no longer expected to reply as quick as possible.

For me, being on a floating island in the middle of vast ocean magnifies the importance of the present. Since there is virtually no communication with the world on land, your life on the ship becomes everything while you are at sea.

Sea life revolves around the schedules we construct, which do not follow the traditional five-day work week, nor the nine-to-five working hours. The date often feels totally insignificant, and because schedules are ever-changing and adapting to the conditions at sea and on the ship, it is difficult to plan details far in advance.

The same goes for people. Living and volunteering on the ship means there are no significant breaks away from your professional responsibilities or your co-volunteers. Most of the Peace Boat volunteers even share rooms with one another. While the nature of this live-where-you-work-environment presents its own challenges, I have really enjoyed it thus far. It is easier to be present without all the technological distractions, which allows you to connect with people in a different, more personable way.

Add this article to your reading list