Ready. Set. The rumble of thunder serves as my start signal.

I am rushing not to evade the downpour, but to catch the boat. I have two hours to return to the lab from the forest, to pick up a book, to sort and freeze my insect bounty, to identify some plants and then take my shower. Then it will have been another full day of work on BCI.

Today, the wind does not wail. There is quiet before the storm. The birds hush for once and the absence of scampering and rustling tells me that most animals have headed for shelter. Some days it feels like a tornado is about to touch down the way the dark forest gets darker and the howler monkeys start to shriek. The clouds converging overhead should be a daily occurrence, but it is not. It is an El Niño year. Although it is the rainy season and the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone is overhead, precipitation is down due to weakened trade winds. Irregular showers and Friday afternoon thunderstorms make for a relatively dry year in Panama.

I am damp all day, regardless, so the prospect of rain is appealing. The air presses down on me when I climb up 13 flights worth of stairs each morning in my long-sleeved shirt and pants. It causes me to stick to leaves, my backpack, mosquitoes. I don’t feel the need to put on my rain jacket when I hear the thunder.

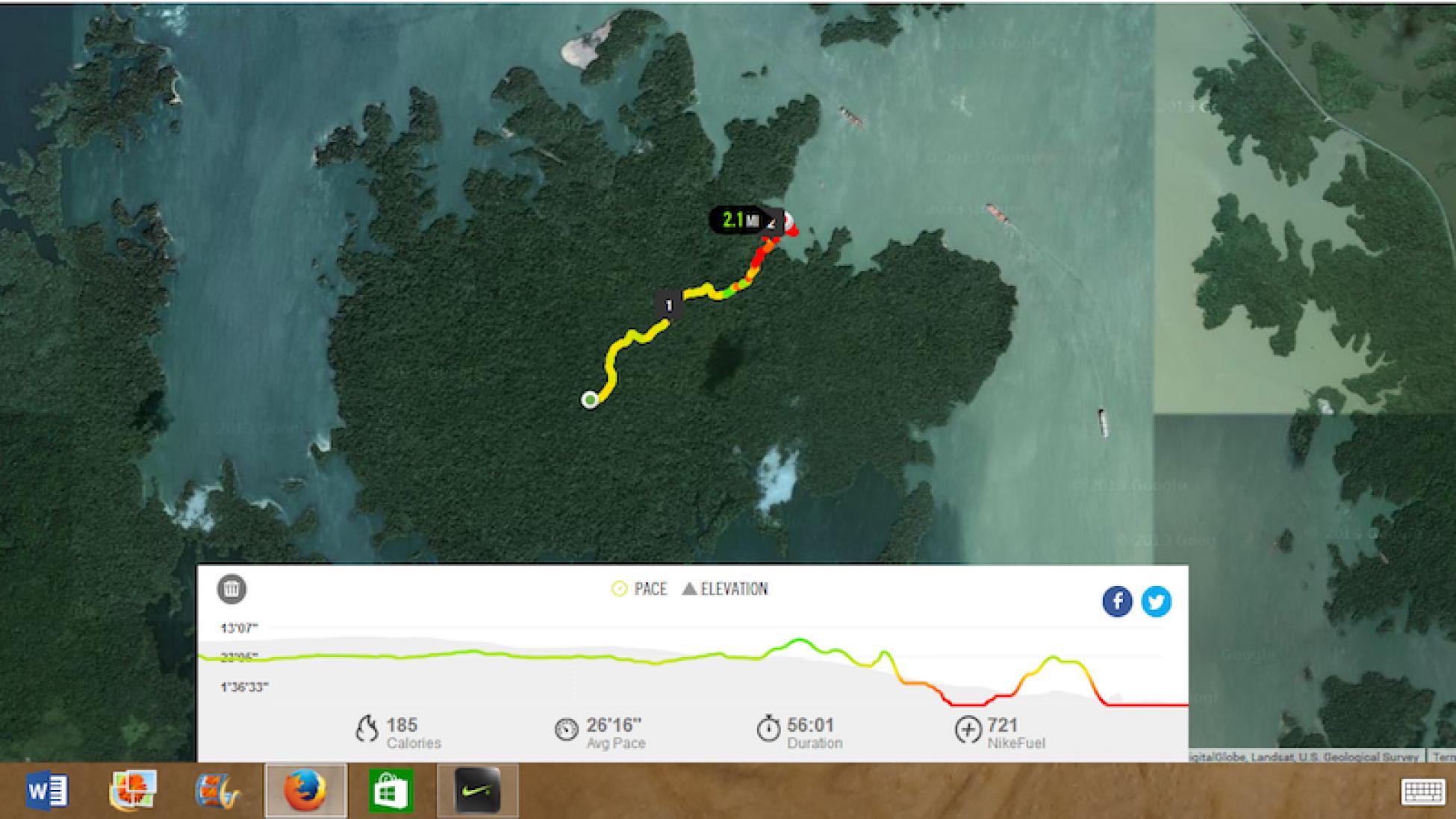

The paths I follow in the forest weave in an attempt to pave the slightest ascent to the central plateau. At times, the kindest angle is 45 degrees. The traverse eases over the course of the day as my backpack lightens when I consume the trail mix, lunch wrap and water. When it is time to return, I have usually been following these trails for six hours. Fortunately, the paths tend to slope down on the way back to the lab.

Just because there are designated trails in the forest, it does not mean they are obstacle-free. There are the liana hurdles, twisted and sprawling, unyielding and crawling with ants. The sliding earth pits demand I place my foot in the exact center of the bottom of the trench. If I am off by an inch, then I have to hope that the yoga sessions in Gamboa have helped improve my balance. The mortar stones are supposed to facilitate my walk, but their spacing forces me to unnaturally extend or compress each stride and would only be helpful if I was walking up against a spontaneous stream brought on by a rainstorm. It happens. The crossing guard bees are fuzzy insects that could easily obscure my thumb and tend to buzz at knee height over a particular part of the path. Like at a red light, I feel safer waiting for the intersection to clear before proceeding.

The bee departs and I walk past in double-time, reaching the spot where I ate lunch with my teammates two hours earlier. No trace remains of the chorizo slice that fell out of my wrap. I had noticed the ants starting their tug-of-war with the sausage almost immediately upon impact with the forest floor. Ripe fruit is not pristine for long either. Even large trees decompose rapidly. This is how the rainforest makes its living.

I hear the rain before I feel it. It approaches like a chain of dominoes as each new curtain of rain breaks through the canopy. I witness the first flash of lightning and think of the thrill of the group working on the effects of lightning on downing trees. I anticipate the sheets of water that will be emptied from the dark clouds and cause the large barges in the Canal to pull to a horizontal stop. I think of the pothole ditches in Gamboa that will fill. I foresee the froggers who will be excited at the prospect of finding specimens tonight in the puddles. I imagine the trees that may fall and block the road. The community would have to band together to break off branches one-by-one so the bus can get everyone home for the weekend. I picture the way the freshly spilled rainwater will condense back into the sky in wisps after the rain subsides. They will make the Canal Zone look like the cloud forests of the mountains.

As I approach the lab, the first drop steaks down my cheek and soon a gentle rain has rolled in, barely slicking the steps. I smell the usual rainstorm smells. The flowers are more fragrant. A fresh dill scent has wafted up from below, masking the pervasive vegetable-that-is-starting-to-go-bad odor. Yet, the trickle remains a trickle. The buildup lasted longer than the rain. I am still slightly wet and not quite cool—there has been no change. Well, that’s El Niño.

Add this article to your reading list